Joan Baker and Sonography

Joan P. Baker is an icon of the sonography profession. A hundred years from now, sonographers will still be able to recite her well-known accomplishments:

Joan P. Baker is an icon of the sonography profession. A hundred years from now, sonographers will still be able to recite her well-known accomplishments:

- She led the creation of the sonography occupation.

- She was the co-founder of the Society of Diagnostic Medical Sonography (SDMS).

- She was twice the SDMS president – the first in 1970-71 and the 14th in 1997-99.

- She was the founder and first chair of the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonography.

- She was a chair of the Joint Review Committee-Diagnostic Medical Sonography.

These are outstanding career achievements; however, knowing them doesn’t mean you know Joan P. Baker, not really. There is much more to her that is worth knowing and remembering: the early formative influences that created her tenacious character, the serendipity of a language course that detoured her from medical school into radiography and then ultrasound, her early career in London and an invitation to the United States, a much storied night in a bar where a vision took root, and decades of unrelenting battles – some won, some lost but all necessary to make the sonography profession what it is today. Surprisingly, at the start and throughout almost 60 years of constant, unsurpassed contributions to American diagnostic medical sonography, she never thought of herself as being “great,” or anywhere close to it. “I don’t recall having dreams or aspirations or anything else. I was busy putting out fires under my feet mainly,” she says. She has worked for the good of the profession, and anyone who derives their living from sonography owes it to themself and to this remarkable woman and champion of ultrasound to take a few minutes to know her by learning her story.

The Early Formative Years: Birth Order and Tennis

Joan was born in Chester, England in 1942. Her father was an auctioneer and, later in his life, an elected official and a captain in the British army. “He did not see us until we were four years old,” says Joan, speaking of herself and her twin sister. “He did not know, and neither did my mother, that she was having twins until after my sister was born. She is 30 minutes older than I am, and I’ve never been allowed to forget it.” Two younger brothers completed the family.

“I went to boarding school with my sister, starting when we were about 10 years old,” she says. A boarding school was the best education available for families that could afford it, and Ockbrook School in rural Derbyshire between Nottingham and Derby was chosen, in part, because of its notoriety in competitive tennis and tennis instruction. “My father was a well-known tennis player in England, and we were born with tennis rackets in our hands. We started to play tennis when we were five and played for Ockbrook, traveling throughout the summers, playing in competitive tournaments. Tennis was probably the root of my competitiveness,” she reflects. “I am very competitive. I don’t like to lose. I don’t like to lose an argument. I don’t like to lose anything.” This quality would prove essential many times over in her career, including in both SDMS presidencies.

Twins Go Separate Ways

Ockbrook, a strict school that offered a rigorous curriculum that included biology, chemistry, math, English, and history, gave the British twins similar inclinations that they took in different directions; however, they both were teachers during their lifetimes.

“After graduation from Ockbrook in 1959, my sister went to London University. She went into X-ray crystallography and eventually worked at Lever Brothers, a well-known company in the United States.” Joan had wanted to go to medical school. “To get to medical school, I had to have a language other than English. I took French and failed it. I didn’t know I could take it again. Nobody told me. So I decided I needed an alternative,” she says. She took radiographers training at the Royal Infirmary, associated with Liverpool University, and earned a British MSR credential in 1960 before moving on to advanced studies in biology and chemistry at Birkenhead Technical College. “It was my choice to stay locally. I was happy to do this,” she says. Joan’s first professional role at a local hospital with 120 beds would put in sharp relief the major contrast that would come later when Joan was hired at the 1,300-bed St. Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, London, which is famous as the birthplace of Britain’s princes, William and Harry. Far more important to our immediate story, St. Mary’s Hospital is the place where Joan P. Baker went through a difficult experience and came out stronger – and feeling able to face anything for the rest of her life.

St. Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, London - photo by Enric via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

An Experience Still Painful, the Crucible of Her Lifetime

St. Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, London - photo by Enric via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

An Experience Still Painful, the Crucible of Her Lifetime

In 1952, about eight years before Joan began at St. Mary’s, at least 4,000 people died in the Great Smog in London, an inversion that trapped pollutants from coal and oil burning close to the ground. Air quality legislation was passed eventually but the fog brought death for several more years; in 1962, 750 people died. In 1960, when Joan arrived, London was under a red warning that restricted hospital admissions to victims of the poisonous air. “People dropped dead in the roads. They couldn’t breathe. I went to London to start a new life during this red warning,” she recalls.

Joan’s father did not approve of her choice of radiography as a career. “He thought radiation was dangerous. He didn’t want his daughter exposed to it. I had to promise him I would obey all the rules, which I did. He said, ‘OK, you go make a living and be successful in the career you chose.’ He didn’t think I could. He didn’t think I was going to earn enough or be able to stand on my own two feet. He told my sister to support my independence and she did by allowing me to find my way on my own during the time we were both in London,” she says.

Alone, her father’s fear of radiation instilled in her, Joan confronted a big city that was paralyzed by the weather. Two or three weeks into her new job, it was Joan’s turn to be on-call – the only radiographer in an enormous hospital on a night that would become a nightmare. A freeze the night before had left black ice everywhere, making London a macabre crisis of acidic fog and black ice. Then things went from bad to worse. A train coming into busy Paddington Station failed to stop at the end of the platform, causing multiple injuries.

Joan recalls what she confronted at only 18-years-old. “I had not stopped to eat that day. I had been taking x-rays one after the other, even before the train wreck. I went downstairs to what we called the Casualty Department, the ER, to tell the physicians I was going to have to eat something because I was not feeling well. There were people lying on the floor everywhere, victims of the train wreck. A physician told me to call my mates (co-workers) and get them in here. There were 21 x-ray technologists. I called them but none came in.” She didn’t have time to feel anything or dwell on what was happening, only to do what she had to do.

“When everyone came in the next day, there was a huge stack of completed X-rays. They couldn’t believe that one person had produced them all,” she remembers. Joan has re-lived that day in her mind over the years, remembering the hunger, lack of sleep and no room to rest, and the faces of the patients, as well as the immense vagaries of being alone to handle a crisis in a very large hospital she arrived at only a few weeks before.

“It was a horrendous day. I came to the conclusion that, after that night, I could take on anything and get through it. There was nothing else that would ever bother me. I think that turned out to be a true statement. It took something to get over it. It’s still a very raw subject to me. The thing that came after that was the strength and the willingness to battle.”

How She Earned Her Ticket to America

Joan’s curiosity – a truly insatiable interest in learning everything she could – and her “never say die” pursuit of expertise par excellence were two of her distinguishing characteristics that would make her an acclaimed pioneer in ultrasound (a modality others had dismissed as a “dead end”). These traits would also be her ticket to the United States.

“I went from St. Mary’s Hospital in London to the National Hospital of Nervous Diseases at Queen Square, which was considered one of the best neurological hospitals in the Commonwealth. The patients there were very sick,” says Joan, who had wanted to specialize in something she hadn’t gotten to do as a student because it was just being invented. That was arteriography/angiography. “There were many famous practitioners there,” says Joan. She witnessed several percutaneous carotid arteriograms performed by her boss, Dr. James Bull.

Surrounded by medical leaders and trailblazing procedures, Joan says, “I had the dubious honor of doing things that other people considered a waste of time; that is, nuclear medicine and ultrasound. It was very primitive. A brain scan took at least three days because of the isotope being used. Ultrasound was just a machine with a bunch of wires. There were a few other people doing ultrasound at the time, but I didn’t know them. I knew I was doing stuff that wasn’t commonly done. I didn’t know it would have any impact.”

In 1964, while 22-year-old Joan was busy with ultrasound and nuclear medicine, Dr. Bull attended an international conference of neuroradiologists, where he talked with Dr. Leslie Zatz, a neuroradiologist at Stanford Medical Center. Dr. Zatz asked Dr. Bull if he knew anything about this new modality of ultrasound. “Well,” said Dr. Bull, “We’ve got this gal in my department who does ultrasound so very well!” Dr. Zatz asked for permission to write her. In 1965, at the age of 23, Joan P. Baker was on her way to America and to Stanford, which she believed would be an Ivy League-like “mecca of ultrasound,” based on informational materials she had read.

In short order, she became aware their knowledge of ultrasound was limited. She was the new resident expert. “I suddenly had a bit of an influx of confidence because, after all, my five years of work in ultrasound was more than they had. It was obvious that they did not know what an ultrasound machine could do,” she says.

-schnitzer---early-70s-scanning.jpg?sfvrsn=43a140ff_0&MaxWidth=350&MaxHeight=&ScaleUp=false&Quality=High&Method=ResizeFitToAreaArguments&Signature=28F68C3431BFDA5B0A43476C47021F6BF3C5A42F) L. E. Schnitzer scanning, early 1970s

An Answer to Professional Loneliness and That Storied Night in a Bar

L. E. Schnitzer scanning, early 1970s

An Answer to Professional Loneliness and That Storied Night in a Bar

After four years of immersing herself in her work at Stanford in Palo Alto and later at Good Samaritan Hospital in San Jose, Joan discovered, “I was professionally lonely, I suppose you could call it. Nobody was aware of others doing ultrasound in the United States in 1969, so there was no one to talk to. She began attending a variety of medical conferences and going on Grand Rounds at Stanford. One of the conferences she decided to attend was in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, and it was hosted by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM). The decision to attend was life-changing.

“The AIUM was in its early days, and it was a mixture of people using ultrasound therapeutically or diagnostically. I went there looking for somebody else who was not a physician and not an engineer – someone with whom I could talk about what we did,” she recalls. One evening, she found five other people to chat with in the bar at the conference hotel. Most of them didn’t know each other. Joan knew none of them before that night.

Besides Joan, there were Marilyn Ball, Margaret Byrne, James Dennon, Raylene Husak, and L.E. Schnitzer. “We talked about what we did and how we did it. There was no manual. It was a surprise to us what we did. We decided we wanted to continue to communicate with one another and to benefit from one another’s experiences. That was the groundwork for, ‘Well, why don’t we form an organization, a Society.’ There already were non-physicians and non-engineers in the AIUM. We were going to build up this category. I don’t know why, in our wildest dreams, we thought we six people could form an organization. We just never thought about that,” she says.

L.E. Schnitzer and Joan Baker

L.E. Schnitzer and Joan Baker

All six shared enthusiasm for the venture but communication logistics being what they were at the time, it was easier for Joan and L.E. Schnitzer to keep things moving forward. Over the next year, he would complete the new Society’s constitution and bylaws and she would register the Society as a non-profit organization.

L.E. Schnitzer had used “technical specialists” as the name for the profession. The hope was that the name would prompt inquiries about the profession and foster interest. “It didn’t catch on, so even while the Society’s name remained the American Society of Ultrasound Technical Specialists (ASUTS), the group had begun referring to themselves as sonographers.” In London, Joan was called a “radiographer,” so the name was adapted into “sonographer,” with sono meaning sound and grapher meaning someone who makes an image or picture. Sonographer seemed to fit and was used in the Society’s name until 1980.

Original ASUTS logo

Original ASUTS logo

It was a year after that storied meeting in a bar that Joan and L.E. presented the documents of the new Society. “When we got to the AIUM meeting in Cleveland in 1970, there were 13 people who were non-physicians and non-engineers who were interested in what we had to present. We all crowded into my hotel room and went through the constitution, every line, every word. It was quite a large document,” she recalls.

The Battles Won and Lost – and Her Finest Achievement

Battles proliferated around the creation and growth of the sonography profession. Looking back, Joan is philosophical but history also demonstrates how shrewd and intelligent she has been in confronting adversity and opposition.

“I think every president of every organization when they get elected is bound to say, at some point, we’re at a crossroads. We’re always at a crossroads. I think the ability to be a good president or a good leader is measured by your ability to look into the future and get there before you need to. The future isn’t something that happens to you. It’s something you engineer and you control. Knowing where things are going and getting a feeling of what you should do is necessary. You won’t be right all of the time, but you want to be right most of the time,” she says.

This philosophy infused not just her two SDMS presidencies but all the battles she undertook. Very early, she developed an approach that she admits may sound calculated but it works. “You have to get the buy-in of key people who are standing in your way or those who can help you – one or the other. Trying to find out what motivated them, what put them where they are, helped me to get around them – that sounds terrible! – or to work with them,” she says, acknowledging that, money and turf battles commonly motivated opposition.

Perhaps the single most important event in the Society’s history – and Joan calls it her finest achievement – is the creation of the occupation. “While the creation of the Society was very important, I think what was more important was the creation of the occupation. There is no point to having a Society if you don’t have an occupation,” she says.

Establishing a new occupation was not easy. The Manpower Division of the American Medical Association, which was responsible for creating new occupations, was disbanding and the tide was turning away from new allied health professions. “When you formalize something, you’ve got to go through a lot of agencies that decide or measure whether you’re fit to be recognized. You have to be able to tell them how many people are going to be involved in this occupation that you’re trying to create. They’re trying to get you to call it something so they can put it under something that already exists. The pressures and stresses were tremendous,” Joan recalls. “There was pressure to put sonography under X-ray technology or some other allied health field so that the wheel would not have to be re-created.”

Joan quickly sought the help of Dr. Gilbert Baum, AIUM president, who interceded with the AMA, which paved the way for a meeting with Dr. Ralph Kuhli, director of the Allied Medical Professions and Services, and members of Allied Medical Emerging Health Manpower of the AMA. In 1973, the AMA’s Manpower Division designated “diagnostic ultrasound technology,” now known as “diagnostic medical sonography,” a new occupation, and it was included in the 2002-2003 Occupational Handbook of the Bureau of Labor Statistics in the Department of Labor.

Joan would continue to confront menacing turf battles and seek to disarm them during the 1980s and 1990s when debate on legislation was at a fever pitch – most strikingly in efforts to create national licensure for sonography and avoid other health professions from calling the shots for sonography through their dominance on state licensing boards.

“To this day, national licensure for sonography still hasn’t been passed. You go to the hairdresser, and she has to have a license to cut your hair. You go to have an ultrasound performed, and the person isn’t licensed and doesn’t have to be certified, registered, or anything else. That, to me, is the saddest thing to have to say after all these years,” Joan laments. “If you had asked me back then if sonography would be a licensed profession, I would have said, ‘Of course!’”

In the 1990s, when Joan was entering her fifties, she decided to dedicate herself to a new cause – safeguarding sonographers from work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMSDs) – and it has consumed half of her career.

“I was sort of made the champion of sonography ergonomics because of a lecture I gave to the SDMS,” she says. “They followed up by sending out a big survey that, to this day, has established that WRMSDs are a worldwide problem.”

Joan’s deep knowledge of healthcare systems in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and elsewhere made it clear to her that the structure of American healthcare is a barrier to reaching a solution. “In the United States, we are committed to fixing the problem one hospital at a time. In countries with more centralized medicine, they can pass a law through occupational health and it applies to the whole country at one time. In the United States, we have to do it piecemeal. That’s why we don’t seem to make much progress. People question, ‘How can you possibly get injured rubbing jelly onto someone’s belly?’ But that is an oversimplification. The problem is more complex,” she says.

Joan jumped into the fray early as equipment manufacturers and hospital administrators blamed each other. Manufacturers claimed there was no reason for them to modify ultrasound equipment if hospital administrators were unwilling to purchase ergonomic beds, tables, and chairs. “What I did was ask them what THEY were doing, to stop the blaming. They started to do things that were long overdue and there was a big shift in their efforts to make the equipment lighter in weight. So, the commercial world has done a lot to try to address this issue, compared to where they came from,” she adds.

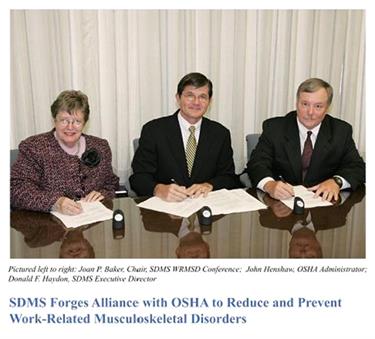

With her international perspective, Joan knew it was essential to tackle the problem on a worldwide stage – in part to keep equipment manufacturers from writing off the American market as just too difficult for business dealings. Joan chaired the first international Consensus Conference on WRMSDs in 2003 in Dallas. The problem continues to grow with 90% of sonographers and vascular technologists scanning in pain, according to research. Joan was a consultant to the Clinton Administration to win passage of an ergonomic rule; but the subsequent Bush Administration rescinded it and relegated efforts to a more ad hoc approach tackled as individual alliances between organizations and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). She and the SDMS Executive Director Don Haydon represented the SDMS and Assistant Secretary John L. Henshaw represented OSHA for the signing of the OSHA-SDMS Alliance in October 2004.

Joan’s impact through the Alliance has been extraordinary in raising awareness of the WRMSD problem in sonography. She reached tens of thousands of people by giving educational presentations on ergonomics in more than half of all U.S. states. She helped drive the inclusion of sonography-related content in OSHA’s Hospital eTool in the Clinical Services module. When OSHA Assistant Secretary Charles Jeffress testified to a Senate subcommittee, it was apparent Joan had knocked on his door many times; the sonography profession was the only industry he singled out in his testimony, making sonographers a national model of the WRMSD problem.

Now 80 years old, Joan continues working fiercely for the musculoskeletal protection of sonographers. She acknowledges that other medical professionals – occupational therapists and physical therapists – are working to treat musculoskeletal injury after the fact. Joan is adamant that sonographers must take responsibility for preventing career-ending musculoskeletal injury. Equipment manufacturers, healthcare administrators, government, and advocates cannot do it all; sonographers must agree to comply with ergonomic practices.

Reflecting on Two Presidencies

In 52 years, from 1970 to 2022, only two people have served as president of the SDMS more than once: Joan P. Baker (1970 to 1972 and 1997 to 1999) and Jean Lea Spitz (1987 to 1989 and 2005 to 2007). “My two presidencies were very different,” says Joan. “With the first presidency, whatever you did, it was the first time being done. It was the first go-around. By the second presidency, we had become a lot wiser.

“This is not a one-man show. You have to get grassroots support to do anything. One person gets the recognition but it’s really a whole cadre of people. By the second presidency, we had been thrust against our will into the political arena, becoming so involved in the legislative process and in legislation. I think I was elected the second time because I had “been there, done that.” I had the experience, not the success and not because I was anything special.

“I feel sorry for the people who elected me to the second term thinking I had ‘been there, done that’ because it didn’t make any difference. That was no ticket to success the second time around. A lot of kudos deservedly go to the SDMS staff and board. They were all very much involved in the success and in increasing membership. Stephen McLaughlin, the president who followed me, he was amazing. His contribution was to boost membership. All the presidents had talents and they used those talents.”

Witness to Differences in Behavior and Values

Since she arrived in America in 1965, the different approach to healthcare is not the only contrast Joan has seen between England and the U.S.; in addition, she has seen a panoply of changes in American culture, attitudes, and behavior.

When she arrived to work at Stanford, the medical center sent a nurse with a placard and her name to the airport in San Francisco to pick her up. They drove down the freeway and the 23-year-old ultrasound and nuclear medicine specialist had her first impression of the United States. “I remember seeing this enormous sign (by the freeway). I’d never seen anything like it. Things are much smaller in England. This sign said, Buy Your Plot Now. It was one thing to see a great big sign and another for it to say Buy Your Plot Now. That was my introduction to America,” she says. In England, when people visit cemeteries, it is to look for the tombstones of ancestors. In America, she discovered that people would buy plots and tombstones well ahead of time. “They weren’t dead. They were still alive.” This approach surprised Joan and has remained a vivid memory for over 50 years.

There were more surprises when she walked into Stanford and was greeted by many people, all hugging her. Not surprising to an American, maybe. “Things like that aren’t done in England. I thought, Oh my gosh. I’ve been brought to some strange place, you know. How could people hug you when they don’t even know you? In England, you have to be around a month before they even acknowledge your existence, let alone whether you get a hug.”

In Cleveland in 1970 when the Society was officially created, Joan remembers, “I was pleasantly surprised that so many people were of the same mind as I was and felt this new Society was needed. We were champions of this modality of ultrasound because nobody else knew what we were looking at. We were looking at spikes on a screen coming from the body, from the tissues.” There was a pioneering spirit that was widespread among sonographers in the early days that sonographers today may not get to experience in the same way, she believes.

“We had a kind of excitement and a feeling of discovery upon seeing images for the first time. Then it was sort of a prerequisite to being a sonographer. You had to really want the challenge, to be a good detective. You had to know some basic medicine, and you had to listen to people who didn’t believe in what you were doing,” she says. A strong sense of partnership formed between physicians who needed the images and the non-physicians who made them.

“A physician was responsible for interpreting the images but was not part of making them. The sonographer got to produce the image and producing it gave a better understanding of what was being looked at. A physician and a sonographer would often spend time reading together because this was the missing link between the physician and the sonographer who created the images,” she remembers.

A Sonography Love Story

Joan P. Baker has earned the appreciation of a grateful sonography profession and world. Her many accomplishments and honors are only a beginning in illuminating her substantial contributions to a profession she fought hard to establish. She has won top awards from the SDMS: first Fellow, Distinguished Educator Award, and Joan was the first recipient of a pioneer award established by the SDMS that was subsequently named after her. The Joan P. Baker Pioneer Award was created to honor sonographers who have made innovative and outstanding contributions to the sonography profession. The AIUM has recognized her with its Sonographer of the Year Award and for her outstanding service in the field of ultrasound. She has chaired international consensus conferences, led delegations to Australia and China, and been invited to speak to medical and scientific forums around the world, including Moscow and Brazil. In 1975, she was listed in the World Who’s Who of Women.

Her life has been such a boundless labor of love to sonography, so it is gratifying to learn that in the very early days – the first AIUM meeting she attended in Winnipeg in 1969 – sonography and a wonderful twist of fate gave Joan her own love story by introducing her to the man she would marry, her beloved husband, Donald Baker.

During one of the AIUM 1969 meeting events, Joan was given an opportunity to cross a stage and be introduced to the ambassador from New Zealand and AIUM President Dr. Dennis White. A master of ceremonies at the head of the line of people awaiting introduction looked at their name badges as he announced each in turn.

“There was a man at the top of the stairs with me when I was waiting to be introduced,” says Joan. “The master of ceremonies introduced ‘Dr. and Mrs. Baker,’ and I looked around to see who he was referring to. The name badge of the man next to me said Donald Baker and mine, of course, Joan P. Baker. We didn’t make a fuss in front of the ambassador. We walked across the stage together. Later, it was like, who are you? How two people with the same last name could be in the same field, a field that was so small, seemed rather interesting.”

Fate had much more planned for them. Joan had ruptured her eardrum when she flew to the conference in Winnipeg, so Dr. Brown arranged emergency care and alternative travel home (planes flying below 10,000 feet and trains) for Joan. “Being a true gentleman, Donald Baker, a prominent bioengineer, agreed to come with me as far as Seattle. This was in October of 1969 and we were married July the 4th of 1970. As I told him, it was the only day he could get an Englishwoman to surrender. Dr. Ross Brown, to this day, claims credit for what would happen, that we would get married. It was on his watch and his meeting that it occurred. That’s the story of Donald’s and my courtship.”

Their marriage spanned 50 years, until Donald’s death in 2020, and they had two children together, a son, the fourth Donald Baker in the family tree, and a daughter, Tanya. Their son, a University of Utah graduate, played minor league baseball after college and later became a business manager. Tanya graduated from the Leavey School of Business at the University of Santa Clara and today works as a chief financial officer in Seattle. Before the senior Donald Baker’s passing, he and Joan welcomed six grandchildren.

In October 2022, Joan flew to Winnipeg to stay in the same hotel where six non-physician, non-engineers stirred the first notions of a Society to keep them and others like them connected and contributing to ultrasound, a modality they believed in when many others didn’t.

From Winnipeg, Joan reenacted her 1969 trip to Vancouver and then to Seattle, this time without Donald.

“I just decided I wanted to do that,” she says. “These past few years, I have been reliving experiences, including some of the things I did as a child. I went to England for two months and went back and saw the houses where I used to live and the school I used to attend, and the holidays we used to take. My brothers assisted me in that. So the last thing I did was this train trip across the Canadian Rockies. It felt like the perfect thing to do at this stage of my journey.”

Joan’s incredible journey continues, forging the next chapter in the story of a remarkable woman who has touched countless lives and been sonography’s champion around the world.